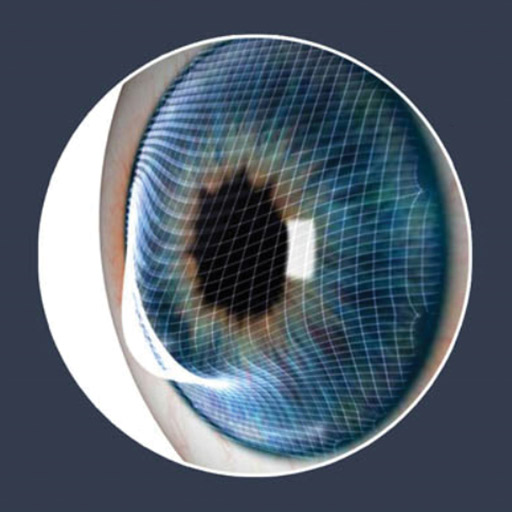

This condition is characterized by a progressive thinning of the cornea which is the clear layer over the Iris. The thinning causes the cornea to “bulge out”, which “distorts” the vision. As the light entering the eye is not passing through a smooth regular surface, but rather through a warped distorted cornea, the effect is like looking through a piece of distorted glass. A common misconception that providing stronger spectacle lenses will correct this condition, but due to the irregular corneal surface, and the resulting distortions, the only way to offer a better optical solution is by providing an artificial smoother front surface to the cornea. In the early stages, this can often be achieved with soft contact lenses, but as the condition progresses, satisfactory vision can only be achieved with hard contact lenses, or Scleral contact lenses. Collagen Cross-linking is a procedure that is offered to patients diagnosed with Keratoconus. This treatment strengthens the cornea, and can slow the progression of Keratoconus. Keratoconus develops very slowly, and in most cases, if this condition progresses, and the patient is no longer able to achieve good vision with contact lenses, surgical intervention by means of corneal buckling, or a transplant is the only option.

Signs and Symptoms

The classic symptom of keratoconus is the perception of multiple "ghost" images, known as monocular polyopia. This effect is most clearly seen with a high contrast field, such as a point of light on a dark background. Instead of seeing just one point, a person with keratoconus sees many images of the point, spread out in a chaotic pattern.

As the cornea becomes more irregular in shape, it causes progressive near-sightedness and irregular astigmatism to develop, creating additional problems with distorted and blurred vision. Glare and light sensitivity also may occur. The effect can worsen in low light conditions, as the dark-adapted pupil dilates to expose more of the irregular surface of the cornea. Often, keratoconic patients experience changes in their spectacle prescription every time they visit their eye care practitioner.

At early stages, the symptoms of keratoconus may be no different from those of any other refractive defect of the eye. As the disease progresses, vision deteriorates, sometimes rapidly. Visual acuity becomes impaired at all distances. Some individuals have vision in one eye that is markedly worse than that in the other. The disease is often bilateral, though asymmetrical. There is normally little or no sensation of pain. It may cause luminous objects to appear as cylindrical pipes with the same intensity at all points.

Other Symptoms include:

- Increased light sensitivity.

- Difficultly driving at night.

- A halo around lights and ghosting (especially at night).

- Eye strain.

- Eye irritation, excessive eye rubbing.

Causes and Risks

The exact cause of keratoconus is unknown. There are many theories based on research and its association with other conditions such as allergies and genetic causes however, no one theory explains it all and it may be caused by a combination of things.

One scientific view is that keratoconus is developmental (i.e., genetic) in origin because in some cases there does appear to be a familial association. Some studies show that keratoconus corneas lack important anchoring fibrils that structurally stabilize the anterior cornea. This increased flexibility allows that cornea to “bulge forward” into a cone-shaped appearance.

Many who have keratoconus report vigorous eye rubbing and also have allergies (which cause eye itching and irritation, leading to eye rubbing), however the link to allergic disease also remains unclear. A higher percent of keratoconic patients have atopic disease than the general population. Disorders such as hay fever, eczema, asthma, and food allergies are all considered atopic diseases.

Some studies indicate an abnormal processing of the superoxide radicals in the keratoconus cornea and an involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of this disease. Keratoconus corneas lack the ability to self-repair routine damage easily repaired by normal corneas. Like any tissues in the body, the cornea creates harmful byproducts of cell metabolism called free radicals. Normal corneas, like any other body tissue, have a defence system in place to neutralize these free radicals so they don’t damage the collagen, (the structural part of the cornea), weakening it and causing the cornea to thin and bulge. The keratoconus corneas do not possess the ability to eliminate the free radicals so they stay in the tissue and can cause structural damage.

Stats and Incidence

The National Eye Institute reports keratoconus is the most common corneal dystrophy in the United States, affecting about one in 2,000 Americans, but some reports place the figure as high as one in 500. The inconsistency may be due to variations in diagnostic criteria, with some cases of severe astigmatism interpreted as those of keratoconus, and vice versa.

Some studies have suggested a higher prevalence amongst females, or that people of South Asian ethnicity are 4.4 times as likely to suffer from keratoconus as Caucasians, and are also more likely to be affected with the condition earlier. From the presently available information there is a one in ten chance that a blood relative of a keratoconic patient will have keratoconus.

Keratoconus is normally bilateral (affecting both eyes) although the distortion is usually asymmetric and is rarely completely identical in both corneas.

Between 11% and 27% of cases of keratoconus will progress to a point where vision correction is no longer possible, thinning of the cornea becomes excessive, or scarring as a result of contact lens wear causes problems of its own, and corneal transplantation is required. Keratoconus is the most common grounds for conducting a corneal transplant.

It is found in all parts of the world. It has no known significant geographic, cultural or social pattern.

Treatment

In the mildest form of keratoconus, spectacles or soft contact lenses may help. But as the disease progresses and the cornea thins and becomes increasingly more irregular in shape, glasses and regular soft contact lens designs no longer provide adequate vision correction.

Treatments for progressive keratoconus include:

- Corneal cross-linking. This procedure, also called corneal collagen cross-linking or CXL, strengthens corneal tissue to halt bulging of the eye's surface in keratoconus. (CXL).

- Custom soft contact lenses can be purpose made and fitted during the early stages of this condition.

- Gas permeable contact lenses are the preferred treatment when soft lenses can no longer control the progression of Keratoconus. Their rigid lens material enables GP lenses to vault over the cornea, replacing its irregular shape with a smooth, uniform refracting surface to improve vision.

- "Piggybacking" contact lenses are an option if there are complications with fitting rigid GP lenses, specifically from a comfort point of view.

- Hybrid contact lenses, are hard in the centre and encompassed by a soft skirt. Hybrid lens technology has improved, giving people an option that combines the comfort of a soft lens with the visual acuity of an RGP lens.

- Scleral and semi-scleral lenses are sometimes prescribed for cases of advanced or very irregular keratoconus. These lenses cover a greater proportion of the surface of the eye and hence can offer improved stability. Easier handling can find favor with people with reduced dexterity, such as the elderly..

- Intacs are tiny plastic inserts are placed just under the eye's surface in the periphery of the cornea and help re-shape the cornea for clearer vision. These are sometimes used when keratoconus patients no longer can obtain functional vision with contact lenses or eyeglasses.

- Corneal transplant is the only option when the condition progresses to a point where contact lenses or other therapies no longer provide acceptable vision.